Mystic Arts Dawn of Time Communing With the Dead

I can't assistance only agree with all the praise being heaped on the Guggenheim'southward big Hilma af Klint show. It's cracking, nifty, beyond great.

Assembled in a chronological progression up the museum's screw, the show feels similar both a manual from an unmapped other globe and a perfectly logical correction to the history of Modernistic art—an alternate mode of abstraction from the dawn of the 20th century that looks as fresh equally if it were painted yesterday.

It'due south hard to quibble with the sheer level of painterly pleasance of af Klint's sui generis style. So instead I'll have a moment to focus on why this show feels and so right for right now.

Hilma af Klint, Altarpieces: Grouping X, No. 1, Altarpiece (1915). © Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk.

A Style of Her Own

Office of that has to do with her status every bit a powerfully convincing and long-underappreciated voice. Now happens to exist a very exciting moment in art history, with loads of new scholarship disrupting the erstwhile Paris-to-New York, Modern-to-gimmicky throughline, reconsidering the stories of minorities and the colonized, "outsiders" of all kinds, and as well of women.

Af Klint'due south body of work really simply began receiving attending in the 1980s and is merely at present getting the kind of widespread acclaim it really deserves—she doesn't even characteristic as a footnote in the catalogue for MoMA's "Inventing Abstraction" show, and that was but five years ago! She therefore fits comfortably within the rediscovery zeitgeist.

Born in Sweden in 1862 and descended from a distinguished clan of naval heroes and maritime cartographers, she trained formally as a painter at Stockholm's official academy. The Guggenheim exhibition opens with a small sample of her landscapes and portraits, which show a deft, accomplished naturalism.

Hilma af Klint, Untitled Series: group Four, the Ten Largest, No. 7, Machismo (1907). © Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk.

But the works she turned to in her forties, similar "The Ten Largest" (1907), are something else over again. The suite of 10 wall-filling paintings represent an abstract symbolic depiction of the cycle of life: the get-go two represent childhood, followed by panels representing youth, adulthood, and old age. Full of wheeling abstract figures, they are nevertheless wonderfully balanced, both in their individual compositions and within the broader series.

They are also, to a contemporary centre at least, very feminine, in a way that stands as a pre-rebuttal of the machismo that later came to dominate abstruse rhetoric as it rose to art historical preeminence. The works of "The Ten Largest" are not figurative, only the forms they channel—the blossoms, lacy garlands, and curlicues; the looping, cursive lines of cryptic text that surge across the surface; the palette of pinks and lavenders, peaches and babe blues—draw freshness, to a contemporary eye, from their symbolic associations with feminine iconography.

Installation view of "The 10 Biggest." Image courtesy Ben Davis.

At the same time, all this is splashed at such a brazen scale that it also undoes menstruation stereotypes of feminine modesty and decorum—though this unleashed expressive freedom was probably itself fabricated possible by the fact that af Klint hardly ever showed these works publicly.

Channeling Brainchild

And so there'south that: Hilma af Klint'south case shows the symbolic power that a woman creative person could depict both in spite of and because of the constraints put on her by her fourth dimension period and her culture, making her a convincing heroine for today. Only there is some other aspect of Hilma af Klint that makes her oeuvre enter into harmonic relation with the nowadays.

That is her occultism.

Af Klint's interior life, I assemble, remains a flake of an enigma, glimpsed through hints and fragments in her journals. What is definitely known is that she had begun attention séances as a teenager, using them as a way to contact her younger sister, who had died young. Af Klint's plough to abstraction grew from experiments with contacting the expressionless, specially as part of a group of women who christened themselves the 5, going into trance states or channeling with a machine called a psychograph.

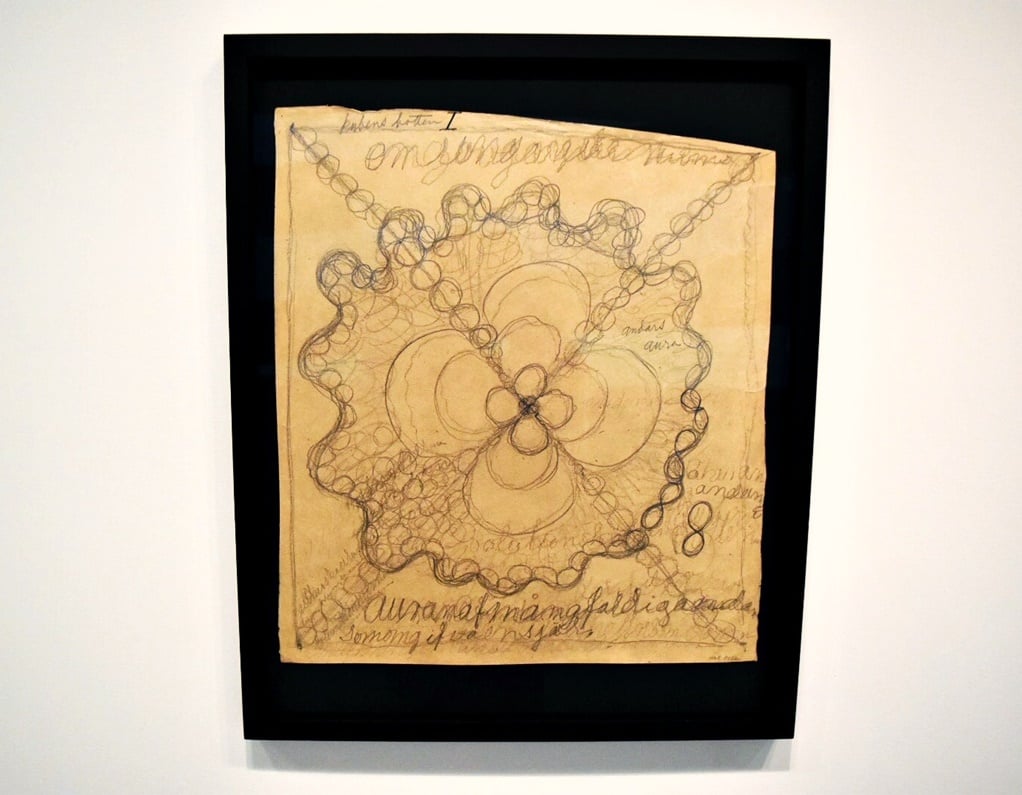

Example of automatic drawing created by The Five. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The spirals, percolating patterns, and scrawled text fragments of the Five's automatic pencil drawings appear like the central chaos out of which the bold abstraction of "The X Largest" emerged.

The Five believed they had been contacted by the "High Masters," spirits called Amaliel, Ananda, Clemens, Esther, Georg, and Gregor. One of these would give af Klint the mission that would get "The Paintings for the Temple," the multi-part bike that occupies most of the Guggenheim prove. "Amaliel offered me a commission and I immediately replied: yeah," she wrote. "This became the great commission, which I carried out in my life."

Occult Modernism

Though unique and all her own, af Klint'south spiritualist passions were fertilized in the larger developments in European fin de siècle culture. Early on, the Swedish creative person plant a home as a Theosophist, shortly afterwards that motion opened a society in Stockholm.

Founded in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky (1831-1891), a Russian émigré to the U.s.a., Theosophy was a New Age philosophy avant la lettre. It combined three pillars: advocacy of a universal brotherhood of man; interest in non-Western philosophy and faith as a source of renewing wisdom; and a belief in communing with ghosts. The concluding, according to Blavatsky, was the least important—but very clearly appealed to the spiritualistically inclined af Klint.

Hilma af Klint's "Primordial Chaos" series. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

This improbable synthesis captured the hearts of Americans and Europeans disoriented by the 19th century's concussive changes, in a time when scientific discipline was crowding religion, and electric light, the telegraph, the phonograph, and other world-irresolute developments were altering the textures of life, making the once-miraculous seem abruptly possible.

In speedily evolving Sweden, Lars Magnus Ericsson would found his telephone company in 1876; less than ten years after the Scandanavian nation had the world'south most complex network and Stockholm had the nearly telephones in the earth. In that febrile moment, no wonder people believed that information technology might also be possible to rig a system to listen to voices from beyond!

Hilma af Klint, The WU/Rose Serial: Group I, Primordial Choas, No. 12 (1906-07). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

(Af Klint had good company in Theosophy amid Europe'south Modernist big guns. Wassily Kandinsky, for i, also counted Theosophy as an inspiration, citing Blavatsky in Apropos the Spiritual in Fine art, the pamphlet he wrote that provided the basis for his "non-objective fine art.")

Amongst other things, the Theosophist craze fed on interest in older undercover societies that had shadowed the Enlightenment, specially the legend of the Rosicrucians, supposedly a secret guild promising spiritual cognition to reform flesh, involving both study of ancient mystic traditions and a belief in alchemy.

The esoteric philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), who passed through Theosophy earlier founding his own doctrine of Anthroposophy, reclaimed the ideas of Rosicrucianism every bit a "spiritual scientific discipline," capable of returning a sense of the purpose of humanity to a world grown disenchantingly materialist. Steiner in detail was a huge influence on af Klint—in fact, he was the only person she sought out to show her paintings to (though when she finally convinced him to see them, in 1909, he was shatteringly underwhelmed).

Signs of All Times

All of these interests are key to agreement Hilma af Klint'due south aesthetic. For instance, in 1920, she made a serial of small works that begins with a single circle, half black and half white, chosen "Starting Picture"—the earth every bit a balanced duality, physical and material, nighttime and low-cal.

Subsequent entries in the serial offer like circles, differently divided upwardly between black and white: one divided into four alternate slices; 1 with black crescents framing a white centre; etc. The titles suggest they are supposed to represent different graphs of the great spiritual traditions: "The Current Standpoint of the Mahatmas," "The Jewish Standpoint at the Nascence of Jesus," "Buddha'due south Standpoint in Worldly Life," and and so on.

Hilma af Klint, Series 2, Number 2a: The Current Standpoint of the Mahatmas (1920) © Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk.

What specifically this means, I have difficulty grasping. But the idea quite conspicuously emerges out of the syncretic foment of the greater intellectual milieu—that all world religions are permutations of 1 spiritual background design that is revealing itself.

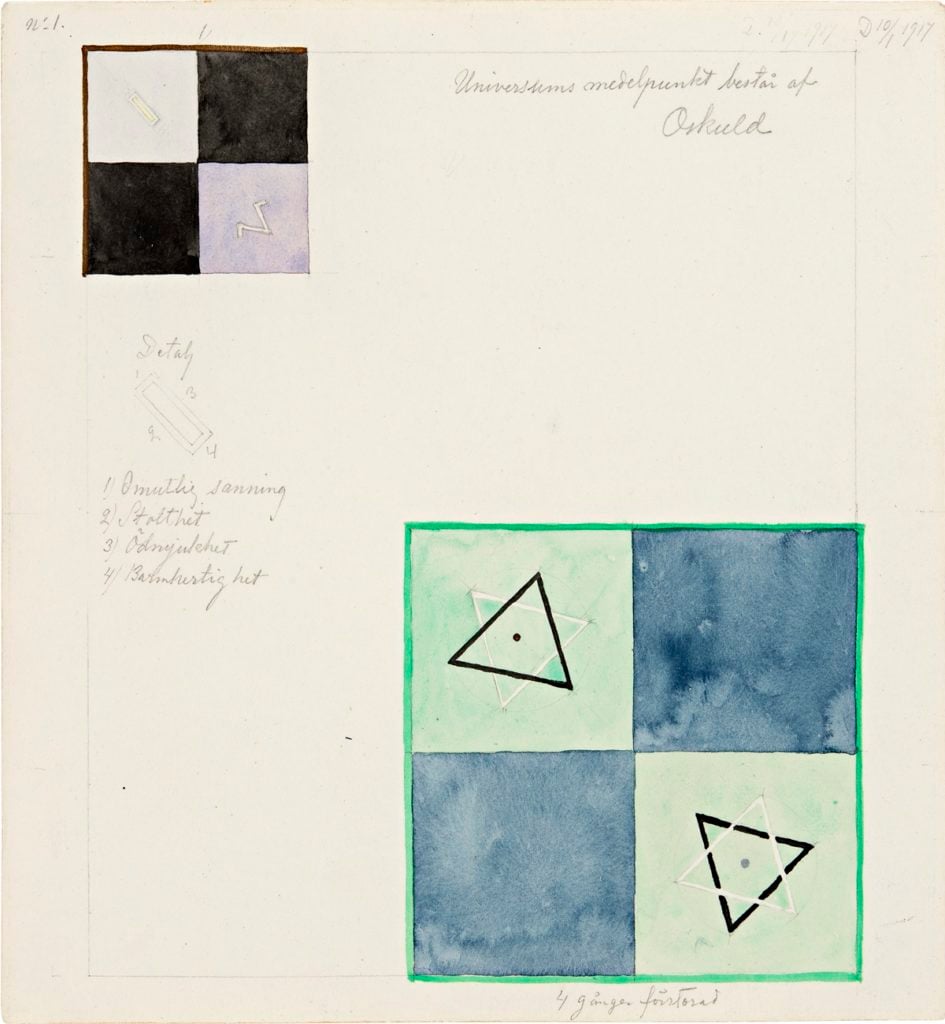

Theosophy was obsessed with esoteric symbols—its seal famously mashed together the swastika and the ankh likewise as the ouroboros and a hexagram formed of interlinked white and black triangles. The latter recurs oftentimes in af Klint's paintings.

Hilma af Klint, The Atom Series: No. i (Nr 1) (1917). Photo by Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation and the Guggenheim Museum. Note the black-white hexagrams at bottom correct.

So practise astrological symbols, another major involvement thrown into the era'south neat melting pot of occult interests. You encounter them arrayed around the borders of paintings in her "The Dove" series.

Hilma af Klint, The SUW/UW Serial: Group Ix/UW, The Pigeon, No. 14 (1915). Clockwise from tiptop left, the symbols are for Aquarius, Pisces, Capricorn, and Sagittarius. Epitome courtesy Ben Davis.

Af Klint's gorgeous series "The Swan" is among the least abstract of her great bike of works, which generally have the feeling of diagrams existence permutated. "The Swan" centers on the paradigm of the titular bird, but mirrored and repeated, transforming it into a hieratic emblem. (In Blavatsky'due south 1890 essay "The Terminal Vocal of the Swan," she had described the symbol of the swan every bit being particularly important, representing "the tail-finish of every important cycle in man history"; in alchemy, information technology stands for the spousal relationship of opposites.)

Hilma af Klint, The SUW/UW Series: Group IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 7 (1915). Note the center pieced by a cantankerous at the center, a Rosicrucian symbol. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Painterly Alchemy

While today af Klint's paintings strike us equally forcefully private, they were certainly starting time appreciated as icons of mysticism. She had but one existent public showing of her piece of work, at a coming together of the 1928 Earth Briefing of Spiritual Scientific discipline and Its Practical Applications in London, where a program noted that the Swedish painter considered her works to be "studies of Rosicrucian symbolism." (Information technology is not known which of her paintings were shown.)

As a font for artistic inspiration, the spiritualist and esoteric domain was certainly fertile. Scissure open the 1785 compendium Secret Symbols of the Rosicrucians, a archetype of European occult literature, and its plates appear every bit a treasure trove of figures that predict af Klint's graphic interests: hexagrams and sigils, sunbursts and spirals, mirrored animals and abstruse figures diagramming the unfolding of the divine light.

Compare the graphics in Secret Symbols'south illustration of "The Tree of Skilful and Evil Cognition" to a work from Hilma af Klint's own "Tree of Knowledge" serial, which offers gnomic variations on the same theme. You lot can definitely see both the inspiration, even every bit you lot see how much more rarified af Klint's version is.

Left: Hilma af Klint, Serie Due west, Nr 5. Kunskapens träd (1915). © Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Correct: Plate from Secret Symbols of the Rosicrucianians of the 16th and 17th Centuries (1785).

Even Hilma af Klint's mandate that her piece of work be kept hole-and-corner for decades later on her death until the earth was spiritually prepare for it is a spin on the myths of Rosicrucianism, which introduced itself in its manifestos equally a clandestine order that had stayed subconscious until the world was ready for its spiritual reform.

Unless yous are a believer in otherworldly visitation yourself, you would probably wait that the cosmic voice within would actually, when decoded, boil down to ideas imprinted from the ambient social environment. This demystifies, merely in no way undoes, the magic of Hilma af Klint'south art.

Message to the Future

So: What to do with Hilma af Klint's art? Can we separate out those aspects that make it prophetic of Modern fine art from those aspects linked to an actual mystical-prophetic belief organization?

The impulse is understandable: The former puts this vibrant artist in the company of the nigh revered creative figures of the century to come; the latter emphasizes elements that connect her more to "kitsch" spiritual aesthetics, fortune tellers and crystal healers and chart readings and all of that.

Installation view of Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

"Taking af Klint seriously as an artist, in my view, actually requires us to take some critical distance from the mysticism that might take enabled her to make such innovative work," art historian Briony Fer argues in the catalogue. I think it undeniable that the sense that af Klint's "Paintings for the Temple" are straining to connect the dots of an invisible lodge is role of their attraction. Fifty-fifty so, I do become that a more formalist reading, focusing on her as an inventive individual, seems the most promising way to brand the case for her in the present.

My argument, though, is that all that occult stuff is what makes her particularly interesting in the present—probably more than interesting than modernists who were outwardly more individualistic and purely formal.

We live today in a time of almost universal domination by the mercenary values of profit, immersed in the cheerful ideology of high-tech disruption and economical creative devastation. We also happen to alive in a time of unleashed irrationalism and improbable conspiracy theories of all kinds, welling upward everywhere.

So it's very instructive to be reminded that all that proto-New Age, occult symbolism that af Klint drew upon did not merely represent a lapse back into pre-Enlightenment superstition. In fact, for thousands upon thousands of people (including many artists), this was the specific form that modernity took.

And information technology was likewise non, more often than not, the grade it took for the poor or unlettered. Theosophy and its kindred philosophies, with their grandiose spiritual pseudo-scientific discipline and their remixing of the world's myths and religions into a master code, appealed, on a profound intuitive level, to people who believed in the authority of scientific knowledge, merely still felt that the emergent mod world left a hole to exist filled in terms of purpose or meaning.

This included relatively well-off and intelligent people like Hilma af Klint, who had time for written report and travel, and resources to embark on a personal artistic-spiritual journeying.

Installation view of Hilma af Klint's "The Pigeon" paintings. Prototype courtesy Ben Davis.

Her beliefs are out there—but on the whole pretty benign and of grade cocky-contained. I'grand non trying to compare af Klint to the more disreputable type of present-day conspiracists or toxic myth-makers.

I'k more trying to say that the example of her work's allusive magnetism tin help united states of america run across one function that obsessions with secret signs and improbably all-connecting codes serve, ane that makes them harder to dislodge than if you simply believe they are logic errors. And that is that they can exist cute. They return a sense of mystery and order to a earth that seems dispiriting and across control.

Hilma af Klint wanted her fine art hidden from the world until society was ready for it. What exactly that would have meant to her remains elusive. And nevertheless, she has surfaced correct on time.

"Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future" is on view at the Guggenheim, through April 23, 2019.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Desire to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to become the breaking news, middle-opening interviews, and incisive disquisitional takes that bulldoze the conversation forrad.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/hilma-af-klints-occult-spirituality-makes-perfect-artist-technologically-disrupted-time-1376587

Post a Comment for "Mystic Arts Dawn of Time Communing With the Dead"